I want you to imagine for a moment walking into a gym full of large, muscular women. They are a little bigger and stronger than you and are also insanely talented at parkour. They can do things that push your previous conception of what humans are physically capable of. You are just starting out in parkour and can only do things at a fraction of the scale they are capable of and with far less confidence. The women are trying to help you learn but offer so much advice that you can hardly think straight. When you approach to join, it feels like you are in their way. Is this level of skill even possible? Where did these super-humans come from?! Is there a special laboratory or something…is Oscorp real?!

All silliness aside, parkour gyms, jams, and events can feel a little like this when first starting out. I am writing this message today to offer some insight from a woman’s perspective on how to create a more comfortable, supportive environment for women within parkour. We do have a strong supportive community already and everyone seems to want to help women feel comfortable. The hope behind this message is to take it to the next level. Ultimately the goal would be to get more women involved in parkour for longer periods of time to reach equal numbers of men and women training. The best way to do this is to create a supportive environment for women and understand some of the differences that women face when trying to get involved in parkour.

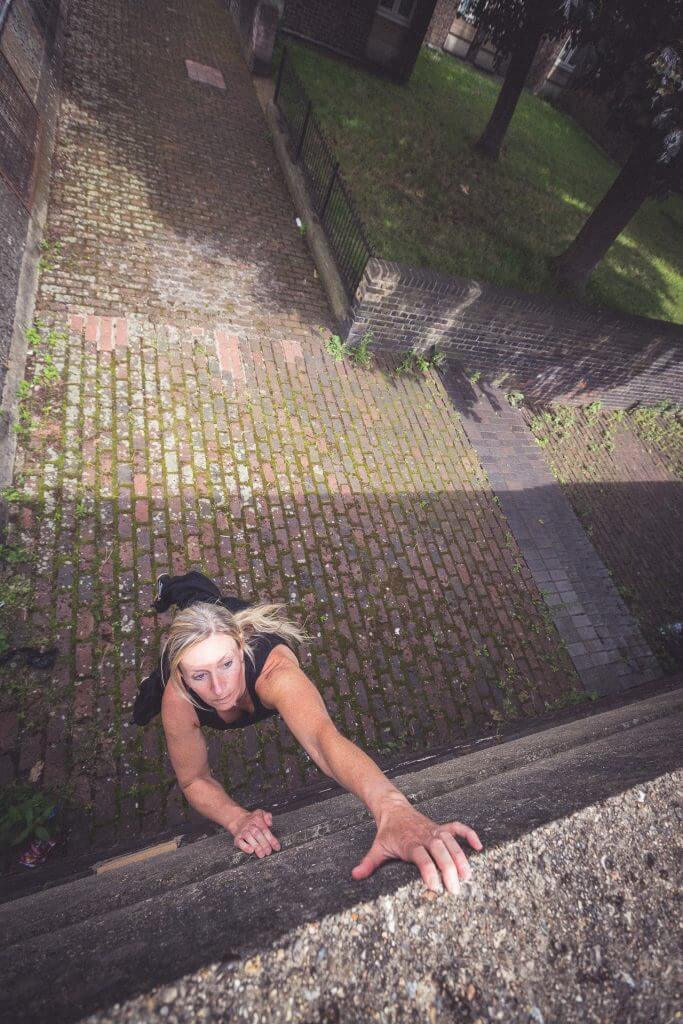

Photo by Andy Day

1. Only Offer Advice When Asked:

(During open gym/jams) Seems pretty simple right? I am not sure what it is about the way we are wired but whenever someone is struggling with a movement, everyone’s initial reaction (myself included) is to look for what they are doing wrong and then tell them about it. I know people offer advice with the intention of helping but in many situations it is not helpful at all; in fact, it can be downright harmful. I think this issue in particular is not specific just to women, I have seen plenty of men in similar situations. Here is a recent open gym experience I had:

At open gym one night there was a mat over the foam pit, making it nearly level to the ground. I was excited to see this set up as I have been wanting to take my side flips closer to flat ground for a while but haven’t been sure how…and suddenly this appeared! What luck! I went up and stood in line with the 8 or so guys that were doing flips onto this mat; mind you they were all doing far more advanced techniques than me so I had a twinge of inadequacy going up there with my not-so-great, very-basic side flip (I have struggled with this flip more than any other and have worked extensively to overcome mental blocks with it). I timidly stepped up with my heart pounding and legs shaking after watching several people throw back fulls, corks, and double side flips, and did my first ever side flip off a six-inch drop (the closest I have been to flat ground before this was around 1.5 inches). Instantly, akin to a swarm of locusts, I had a half dozen people giving me generic advice on how to do a side flip as if it were my first day training.

I can do side flips. They aren’t perfect and there are plenty of things I need to work on, but I can do them. In the past six months I have done hundreds of side flips and probably 30-40 outside. Throughout the course of the evening I heard some variation of the advice, “set higher and tuck tighter,” about 10 times from various people. Since I started doing parkour four years ago, I have heard this EXACT SAME advice THOUSANDS of times. I hear it nearly every time I do a flip in front of anyone. I tried to explain to the spectating advice-givers that I know how to do a side flip and that this is a new situation and therefore it is scary. When I am really scared of things my form deteriorates and I just need to get comfortable with the movement in order to do it well again. Really, I just need a safe comfortable place to practice these. Some encouragement or support would have been like gold in this situation. This can be extremely overwhelming for a person who is already feeling immensely uncomfortable and inadequate. I tried to express some of these feelings and proceeded to get advice on how to handle receiving unsolicited advice. I felt like my head was going to explode and I nearly just walked out and left. I sat for a second and tried to calm myself down but my head was spinning. This was a VICTORY, this was PROGRESS in my training, why does it feel like regression? Have I been kidding myself this entire time? Will I ever succeed beyond basic movements? Do I belong here?

Before offering criticism, think of who you are talking to. Has this person been training for a while? Is it their first day or month? Do they need the same advice as a beginner student? Do they need any advice at all, or do they need support? Someone who is in their first month of training will probably need very different advice than a person who has been training for two or more years and is struggling with mental blocks. People who have been training for a while likely know their technical mistakes, probably better than anyone else possibly could. It seems people usually only offer criticism on technical skills and often neglect the potentially more important internal struggle with fear. Some of the best advice I ever received when practicing parkour was to stop listening to what everyone else was saying and do what works for me. When people are ready for advice, they will ask.

Photo by Julie Angel

2. Offer Genuine, Positive Comments and Support

I don’t think men or women enjoy going to a place where their weaknesses are constantly being pointed out even while they are actively trying to work on them. If you see someone struggling at open gym or a jam and looking really frustrated, look for something they are doing well and tell them about it. It is important to make an effort to be sincere, not just saying something was good when it wasn’t. Also, If you feel inclined to talk with a person, whether it be to get to know them better, help them feel welcome and included, or if you think you can really help them with some information; try opening with a genuine compliment. Look for strengths instead of weaknesses. Pointing out things that people are doing wrong is much easier than finding strengths but their strengths are most likely exactly what they need to hear. I think the interaction will be more well-received since criticism is so openly and often given; a compliment would be refreshing.

I recently read about a study in Sheryl Sandbergs book, “Lean In,” about how men will apply for jobs where they meet 60% of the requirements and women will usually only apply for jobs where they meet 100% of the qualifications. I think this runs a parallel with the way men and women train parkour differently, I often see men who are training (mostly newer practitioners) things they are not ready for or that their bodies aren’t equipped to handle yet. I see the opposite in a lot of female practitioners. It seems women will often only do things they are extremely certain they can do. Our brains are wired differently, we have a lifetime of social conditioning telling us we are not good at sports; that we are weak. Because of these differences women need different things when it comes to support from the community. Often when men are offering me advice, it is usually in the context of “don’t do something bigger than you are ready for.” Which makes sense because they are probably drawing on their own experience and mistakes they have made in the past. For women, I think our mistakes lie more in not achieving our full potential. Nearly all the parkour gym owners, coaches, and practitioners are male so women rarely have the opportunity to learn from other women. We usually only get advice and help from men who are inherently teaching from a male perspective and may not even be aware of some of the different mental battles women face when practicing parkour.

Photo by Julie Angel

3. Understand The Skill Level Gap, And Why It Exists

One of the important things to understand that makes women uncomfortable is the skill level gap between men and women. This gap doesn’t come from women being inherently incapable. Sure, there are biological differences that give men an athletic advantage but it does not account for the size of the current skill level gap. One reason the gap is so vast is because more men have been involved for longer periods of time which inevitably creates more capable male athletes. When trying something new it is human nature to look for examples similar to ourselves who have succeeded at whatever it is we set out to do. It is possible to find examples of successful female parkour athletes but the numbers are small and they usually aren’t at the same level as the top level men in the world. They seem to be a few years behind…probably because they are! It is very difficult to find women who have been training longer than a few years but there are plenty of male athletes in the world at the 6-10+ year training mark. This is a very powerful and exciting realization to have. In the next five years or so when more women reach higher levels of mastery in their training, we will see some pretty cool stuff coming from the women’s community.

Due to social conditioning surrounding athletics and other factors associated with being a woman in parkour, many women seem to be more cautious in their training. Cautiousness is often translated as inability and those beliefs are reflected back to the practitioner in the form of criticism or lack of praise. Men seem to be more willing to commit to something they aren’t entirely sure they can do and will likely receive more praise and less criticism from their coaches and peers resulting in the belief that they are capable of doing this sport. That belief is fundamental to pursuing parkour long term and in a serious way. This kind of thing may be why so many women try parkour but not too many stick with it; and those who do usually already had a strong athletic background in the first place.

Another contributor to the gap (and women losing interest in parkour) is the inability to find peers. The peer relationship is essential to progression and maintaining the element of play. When training constantly with people who are more advanced, it is hard to keep feelings of inadequacy at bay and it is at times like training alone. If you can’t work on the same things everyone else is working on you can’t build off each other and you are left to create your own route entirely. When training with people of much lower skill level it is hard to not be teaching and leading the whole time and once again you cannot work the same movements together.

When it comes to men and women being peers, I have found that men usually start doing things at a larger scale more quickly and to many people skill is determined by scale. It is easy to see and measure, and sure scale is valid, but it is only a part of a person’s overall ability. It takes more perceptive and an experienced athlete to notice subtle advances in technique and therefore it is often unrecognized. This results in the person with the bigger jump believing they are farther along in their training, which often leads to a lot of unsolicited advice, destroying the peer dynamic. I have rarely found men or women who are at the same scale AND technical skill as myself, though it has happened more often with other women which is why women’s jams and events are a great way to meet potential peers.

I think the main key to overcoming the gender gap is to simply forget about gender. Once you train with someone, it doesn’t matter what sex or gender they are. Treat them as an athlete, not as a female athlete. The same goes for women. If training parkour – don’t think of yourself as the only woman in the gym training parkour – think of yourself as an athlete.

– Lynn Jung

Photo by Anya Chibis

4. Don’t Use Sexist Language

I don’t think this needs a lot of explanation but saying things like, “man up”, “grow some balls”, or “quit being a pussy” can create an environment that makes women uncomfortable. A lot of people try to justify this under the guise of joking, but even if it is a joke, the repetition of hearing this language constantly throughout a lifetime can subtly seep into your subconscious. This kind of language perpetuates the antiquated notion that women are inferior, or they are less capable athletes; less courageous.

Women should also stop using sexist language. I have often heard things at the gym like, “I can’t do it because I am a girl” or “you can do it because your a guy.” My personal favorite was an instance at the gym where a girl was urging a guy to do something I had done minutes before, and saying “she did it so you have to be able to do it too.” Each time we use this kind of language it instills the belief that women are inferior athletes. Renowned freerunner, Lynn Jung makes a great point, “Using hashtags such as “girlparkour” also create their own sexist language, not being aware what damage this can cause either. By saying “girlparkour” we define “normal” parkour as “guyparkour”. While positive sexist language can have the advantage of making girls more visible within the sport (probably only within the female community), it longterm makes it harder for female athletes to establish themselves as athletes rather than female athletes.”

Photo by Anya Chibis

5. Don’t Offer To Spot Unless Asked

Spotting has it’s place and can be useful in some situations. However, I have seen a lot of men offering to spot women on movements that I am not sure could even be spotted, or in situations where it could potentially be more dangerous for them both when spotting. For example, spotting on something like a precision or a kong precision just seems like a disaster waiting to happen. When doing a kong precision, we are taught to adapt through many different parkour ukemi techniques like bounce backs, falls from slipping, or bouncing back to a cat hang, which if a person were to do and also have a person trying to catch them, it just adds another variable. You now have to worry about not stomping that person in the face and cannot react as you instinctively would because another person is trying to catch you.

In conclusion, the most beneficial thing we can do as a community is to provide a supportive environment for women to train. This requires having some restraint with unsolicited advice (most men don’t seem to like this either) and putting yourself in her shoes. That being said, in the past few years women have really begun to have more presence in parkour with athletes like Aleksandra Shevchenko (Sheva) who is creating groundbreaking new moves that play to some of women’s physical strengths. There are a number of other women who are making a big impact on the sport right now and I expect we will only see more of that in the coming years. Check out Sheva’s most recent video.

You can also read the book Lean In: Women, Work, and the Will to Lead by Sheryl Sandburg if you are interested in learning more about gender equality.

Another great advocate for women in movement is author and filmmaker Julie Angel’s website See&Do.

Fantastic article–thanks for the read! A lot of really applicable advice in here, for any athletic scenario and beyond. I really appreciate this advice being put out here, and promoted!

Any advice for getting women to start training?

josh, show them something simple and safe. If they look interested, you could explain the technical element of it (ie, not make it look like u see them as an idiot while also pointing out the desired results for best tech) then encourage them to giving a shot. If they do, praise them for their effort and make them feel valued. Then maybe suggest that they ask if they want more advice and get on with your own training – preferably something technical vs something flashy. That approach makes it more accessible. The other ideal is the see&do philosophy – women are more likely to try if they see other woman doing. Maybe get two friends to give it a go at the same time.

If she want to, she will train (hard). You don´t have to force it or something. I know lot of guys who want their girlfriend to start training. I don´t know if this is your case but try to think- why do you want her to train? To spend more time together? To have common hobby? Well! But lot of guys just want their girlfriend to look better, to be trophy they show to their friend etc.

Beautiful article! it actually describes situations that we see pretty often while training either as traceuses and as suporters/instructors.

Great article. Your insight is always appreciated and will keep in mind when practicing with ALL my fellow practitioners. Thanks!

It seems to me that most if not all of the points raised in this article are relevant to anyone beginning and progressing in parkour (female/male, younger/older, athletic/not athletic, experienced/less experienced, skilled/less skilled, etc.). During my brief year and a half with parkour, I have found the several parkour communities I have encountered to be welcoming and supportive to everyone and the diversity is part of what makes it so much fun.

Love this article. Love this sport. ‘Nough said!